A federal appeals court has lifted a block on a Louisiana law mandating the display of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms, paving the way for the posters to appear in schools across the state. The decision by the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, released on Friday, came in a 12-6 vote that reversed a lower court's injunction from earlier in 2024. The ruling allows the law, signed by Republican Gov. Jeff Landry last year, to take effect while litigation continues, marking a significant step in ongoing debates over religion in public education.

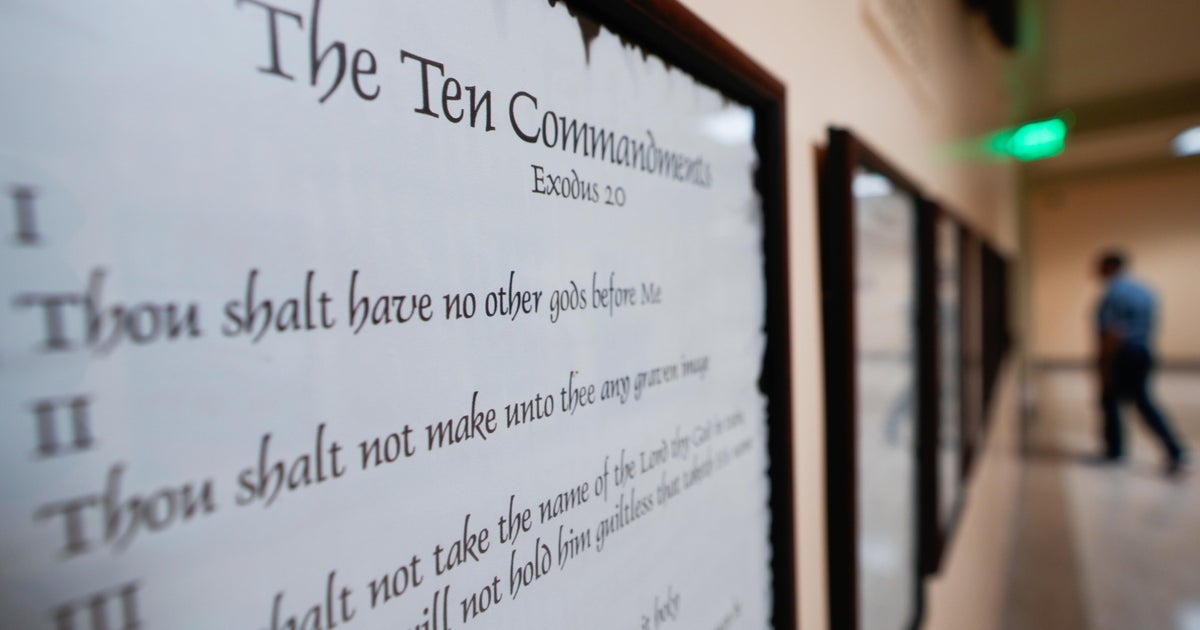

The law requires that poster-sized reproductions of the Ten Commandments be displayed in every classroom in Louisiana's public schools, from kindergarten through universities. Proponents argue the displays serve an educational purpose, highlighting the commandments' historical role in American law and governance. Critics, however, contend that the mandate violates the First Amendment's Establishment Clause by promoting religion in a government-funded setting where attendance is compulsory.

In its majority opinion, the appeals court panel emphasized that it was premature to rule on the law's constitutionality without more details on implementation. "Without those sorts of details, the panel decided it didn't have enough information to weigh any First Amendment issues that might arise from the law," the court wrote. Specifically, the judges noted uncertainties about how prominently the displays would be placed, whether teachers would reference the text in lessons, and if accompanying historical documents like the Mayflower Compact or the Declaration of Independence would also be shown.

The court concluded that the available facts were insufficient to "permit judicial judgment rather than speculation." This procedural move sends the case back for further development, potentially including more evidence on how schools plan to comply. The decision follows oral arguments heard by the full 5th Circuit in January, after an initial three-judge panel had deemed the law unconstitutional in a preliminary ruling.

Dissenting judges sharply criticized the majority's approach. In one dissent, Circuit Judge James L. Dennis argued that the law represents a direct endorsement of religion by the government. "The law 'is precisely the kind of establishment the Framers anticipated and sought to prevent,'" Dennis wrote, echoing concerns about coercion in public schools. Other dissents contended that the case was ripe for review, asserting that the mere requirement to display the religious text in required educational spaces imposes a clear constitutional burden on students of diverse faiths or none.

Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill celebrated the ruling in a statement issued Friday. "Don't kill or steal shouldn't be controversial," Murrill said. "My office has issued clear guidance to our public schools on how to comply with the law, and we have created multiple examples of posters demonstrating how it can be applied constitutionally. Louisiana public schools should follow the law." Her office's guidance reportedly includes suggestions for contextual framing to emphasize the commandments' historical significance rather than religious doctrine.

The Louisiana law is part of a broader wave of similar measures in Republican-led states. Texas implemented its version on September 1, 2023, becoming the largest such effort in the country. Despite federal injunctions blocking displays in some Texas districts, many schools have proceeded by funding the posters themselves or accepting private donations, with the displays already appearing in classrooms statewide. Arkansas has enacted a comparable law, which is now facing its own federal court challenge.

These initiatives align with pushes by Republican lawmakers, including former President Donald Trump, to integrate religious elements into public education curricula. Supporters maintain that the Ten Commandments form a foundational part of U.S. legal and moral traditions, predating the Constitution. "The laws are among the pushes by Republicans... to incorporate religion into public school classrooms," as reported in coverage of the trend. Backers often cite the document's influence on early American jurisprudence.

Opponents, including families from Christian, Jewish, Hindu, and nonreligious backgrounds, as well as clergy members, have filed lawsuits arguing the displays coerce students into religious observance. The challengers in Louisiana include parents and advocacy groups like the American Civil Liberties Union, who sued shortly after the law's passage in June 2024. They assert that the mandate lacks a secular purpose and primarily advances a religious agenda, potentially alienating non-Christian students in a diverse state.

Historical precedent looms large over the dispute. In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a Kentucky law requiring Ten Commandments displays in public school classrooms, ruling it violated the Establishment Clause. The court found the measure had "no secular purpose but served a plainly religious purpose." Two decades later, in 2005, the high court revisited the issue in cases involving Kentucky courthouse displays, deeming them unconstitutional for lacking historical context. However, in the same term, it upheld a Ten Commandments monument on the Texas Capitol grounds, citing its longstanding presence and integration into a broader display of historical markers.

These mixed rulings have fueled ongoing litigation, with lower courts often grappling with the nuances of context and intent. In Louisiana, U.S. District Judge John W. deGravelles initially blocked the law in November 2024, describing it as "a religious display by any reasonable observer's lights." His injunction cited the 1980 Stone v. Graham decision as binding precedent, but the 5th Circuit's en banc review overturned that stay, at least temporarily.

The appeals court's decision injects uncertainty into school planning as the academic year progresses. Louisiana educators must now navigate compliance amid potential further appeals. State officials have emphasized that the posters should include explanatory text about the commandments' historical role, such as their display in early U.S. government buildings. Yet, without finalized guidelines from higher courts, some districts may hesitate, fearing future liability.

Beyond Louisiana, the ruling could influence similar cases. In Texas, where displays have proliferated despite legal hurdles, advocates on both sides watch closely. Challengers there, represented by groups like Americans United for Separation of Church and State, argue that self-funded posters still constitute state endorsement since schools provide the space. Proponents counter that voluntary displays with historical framing withstand scrutiny under the Supreme Court's evolving standards.

The broader implications extend to national debates on church-state separation. With Republican gains in statehouses post-2022 midterms, measures blending faith and education have surged, from school prayer revivals to Bible literacy classes. Critics warn of a slippery slope toward theocracy, while supporters decry judicial overreach in erasing religious heritage from public life. As one dissenting judge noted, the Louisiana law forces children "to confront government-endorsed religion in a place they are required to be," raising questions about inclusivity in increasingly pluralistic America.

Looking ahead, the Louisiana case is likely headed back to district court for trial, where plaintiffs can present evidence on the law's impact. An appeal to the Supreme Court remains possible, especially given the court's recent conservative majority and signals in cases like Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022), which expanded accommodations for religious expression in schools. For now, as posters potentially go up in Louisiana classrooms, the tension between history and faith continues to define this chapter in American education.

The ruling underscores the enduring controversy of religious symbols in public spaces. While Louisiana moves forward with implementation, the legal battle promises to shape policies in other states. Educators, parents, and policymakers alike await clearer guidance, balancing constitutional mandates with calls for moral instruction in an era of cultural division.