In a groundbreaking study that challenges long-held assumptions about brain development, researchers have identified five distinct 'epochs' in the human lifespan during which the brain undergoes significant rewiring. Published on Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, the research pinpoints four key turning points—at ages 9, 32, 66, and 83—marking shifts in neural architecture that influence how we think, process information, and adapt to the world around us. The findings, drawn from analysis of brain scans from nearly 4,000 individuals ranging from newborns to those in their 90s, suggest that cognitive changes are far from linear, with periods of rapid efficiency gains, stability, and eventual fragmentation.

The study, led by Alexa Mousley, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge, reveals that the brain's evolution is not a steady climb to a peak followed by decline, as often portrayed in popular science. Instead, it unfolds in phases, or epochs, each characterized by unique patterns in connectivity and efficiency. 'It’s not a linear progression,' Mousley said. 'This is the first step of understanding the way the brain’s changing fluctuates based on age.'

The first epoch spans from birth up to around age 9, a time of explosive growth. During this period, the brain rapidly expands in gray and white matter, pruning unnecessary synapses and restructuring neural pathways to lay the foundation for complex thought. This foundational phase sets the stage for the more dynamic changes that follow, as children's brains adapt to learning languages, social cues, and basic motor skills.

From ages 9 to 32, the brain enters what researchers describe as an extended era of rewiring, marked by increasingly efficient connections across distant regions. Neural networks communicate rapidly and seamlessly, fostering heightened creativity, problem-solving, and adaptability. This epoch coincides with adolescence and early adulthood, a time when many people pursue education, build careers, and form lasting relationships. However, Mousley noted that this period also aligns with the onset of most mental health disorders. 'Is there something about this second era of life, as we find it, that could lead people to be more vulnerable to the onset of mental health disorders?' she asked, highlighting a potential link between peak rewiring and psychological vulnerability.

Entering middle age, from 32 to 66, the brain reaches a plateau. Here, architecture stabilizes with minimal dramatic shifts, reflecting a stabilization in intelligence and personality traits. Researchers believe this epoch corresponds to the prime of professional and personal life, where accumulated knowledge and experience allow for steady performance without the turbulence of earlier years. The brain continues to rewire subtly, but the changes are slower and less pronounced, enabling consistency in daily functioning.

The fourth epoch, between 66 and 83, introduces a shift toward modularity. Neural networks begin to divide into highly connected subnetworks with reduced integration across the whole brain. This compartmentalization may explain some aspects of aging, such as specialized expertise in certain areas while broader connectivity wanes. Connections that once spanned the brain start to weaken, potentially affecting multitasking or novel learning.

Beyond age 83, the final epoch sees further decline in connectivity, with the brain becoming more reliant on isolated regions. As inter-regional links wither, cognitive processes may fragment, contributing to challenges like memory loss or slower processing speeds. This phase underscores the brain's resilience in old age but also its vulnerability to neurodegenerative conditions.

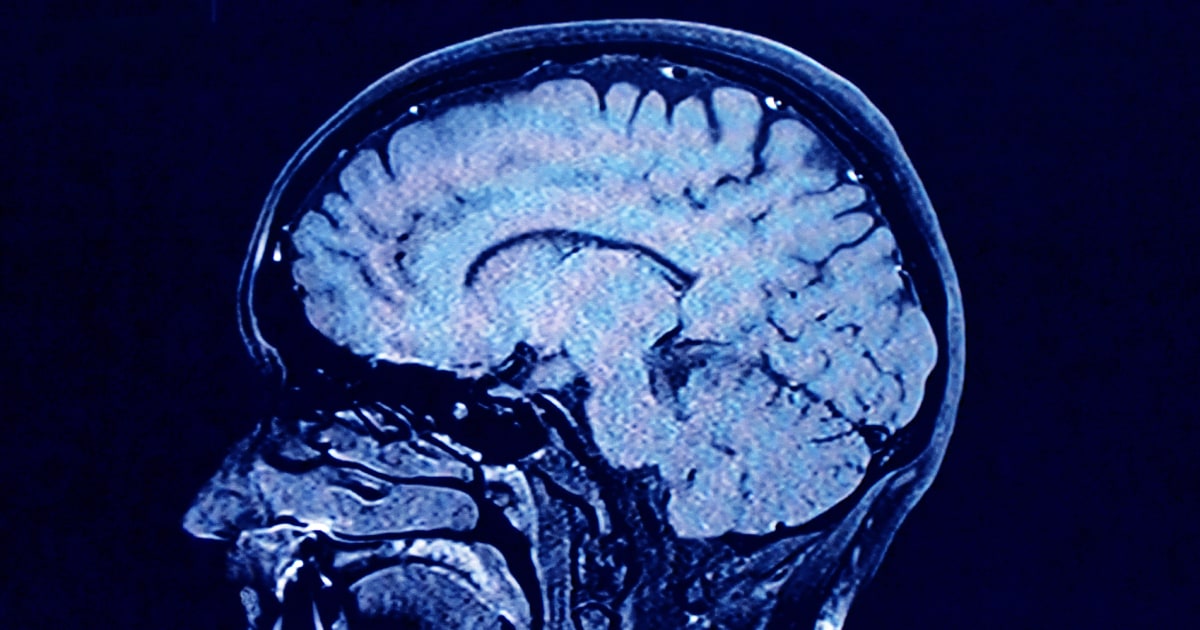

To map these epochs, Mousley's team analyzed MRI diffusion scans from about 3,800 participants, sourced from nine different datasets spanning previous neuroimaging studies. These scans capture the movement of water molecules along nerve fibers, which are insulated by myelin—a fatty sheath akin to wiring in a complex electrical system. 'Water molecules diffused in the brain tend to move in the direction of these fibers, rather than across them, meaning researchers can infer where the neural pathways are located,' the study explains through its methodology.

Rick Betzel, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Minnesota who was not involved in the research, praised the ambition of the work but urged caution. 'They did this really ambitious thing,' Betzel said. 'Let’s see where it stands in a few years.' He noted that while the findings intuitively align with everyday observations of aging—such as parents moving beyond the 'toddler era' with their children—the exact ages of turning points may require further validation.

Betzel emphasized the challenges of the study's design. Ideally, longitudinal data tracking the same individuals from birth to death would provide the clearest picture, but such comprehensive scans weren't feasible due to the relatively recent advent of advanced MRI technology. Instead, the researchers harmonized existing datasets, each varying in quality, sample size, and scanning protocols. 'Each of those data sets varies in quality and approach, and the effort to make them correspond with one another could wash away important variability, ultimately leading to bias in the results,' Betzel observed. Nonetheless, he commended the team's thoughtful approach to mitigating these issues.

The implications of this research extend beyond basic neuroscience, potentially informing clinical practices for mental health and aging. By identifying epochs of vulnerability, doctors might tailor interventions—such as therapy during the 9-to-32 phase to address rising mental health risks or cognitive training in later years to bolster modular networks. Mousley suggested the findings could help pinpoint why conditions like depression, schizophrenia, or dementia emerge at specific life stages, tied to the brain's rewiring patterns.

In the broader context of brain science, this study builds on decades of research into neuroplasticity—the brain's ability to reorganize itself in response to experience. Earlier work, such as studies on synaptic pruning in childhood, has shown how the brain optimizes efficiency by eliminating redundant connections. The new research expands this to the full lifespan, challenging the oversimplified 'use it or lose it' mantra by revealing discrete phases rather than continuous decline.

Critics like Betzel remain optimistic but measured. 'Brain networks change over the lifespan—absolutely. Is it discrete such that there are five exact change points? I’d say stay tuned. It’s an interesting idea,' he said. Future studies could incorporate larger, more diverse populations and advanced imaging to refine these epochs, perhaps adjusting the turning points based on cultural, environmental, or genetic factors.

As society grapples with an aging population— with projections from the United Nations estimating that one in six people worldwide will be over 65 by 2050—understanding these brain epochs becomes increasingly vital. Policymakers and healthcare providers may draw on this work to design better support systems, from education programs emphasizing mental health in young adulthood to retirement initiatives promoting brain health in later years.

Ultimately, the study paints a nuanced portrait of the human brain as a dynamic organ, constantly adapting through life's epochs. While the precise boundaries may evolve with more research, the core message is clear: our minds are not static machines but evolving networks shaped by time. As Mousley and her colleagues continue to explore these changes, their work promises to deepen our appreciation for the brain's lifelong journey.